Recently I was driving to work and thinking about an essay by a statistician on “dropping the stick.” The metaphor was about a game of pick-up hockey, where an inattentive player would be asked to “drop the stick” and skate for a while until they got their head in the game. In the statistical context, this became the action of stopping people who were asking for help with a specific statistical task and asking what problem they wanted to solve, because often solving the actual problem may be actually very different from fixing their technical issue and may require completely different approaches. That gets annoying sometimes when you ask a question to a mailing list and someone asks you what you’re trying to solve rather than addressing the issue you’ve raised, but it’s a good reflex to have: first ask, “What’s the problem?”

Then I realized something even more important about projects that succeeded or failed in my life – successes at radical off the wall projects like the emotional robot pet project or the cell phone robots with personalities project or the 3d object visualization project, and failures at seemingly simpler problems like a tweak to a planner at Carnegie Mellon or a test domain for my thesis project or the failed search improvement I worked on during my third year at the Search Engine that Starts with a G. One of the things I noticed about the successes is that before I got started I did a hard core intensive research effort to understand the problem space before I tackled the problem proper, then I chose a method of approach, and then I planned out a solution. Paraphrasing Eisenhower, even though the plan often had to change once we started execution, the planning was indispensable. The day-to-day immersion in the problem that you need for planning provides the mental context you need to make the right decisions as the situation inevitably changes.

In failed projects, I found one or more things – the hard core research or the planning – wasn’t present, but that wasn’t all that was missing. In the failure cases, I often didn’t know what a solution would look like. I recently saw this from the outside when I conducted a job interview, and found that the interviewee clearly didn’t understand what would constitute an answer to my question. He had knowledge, and he was trying, but his suggested moves were only analogically correct – they sounded like elements of a solution, but didn’t connect to the actual features of the problem. Thinking back, a case that leapt to mind from my own experience was a project all the way back in grade school, where I we had an urban planning exercise to create an ideal city. My job was to create the map of the city, and I took the problem very literally, starting with a topographical map of the city’s center, river and hills. Now, it’s true that the geography of a city is important – for an ideal city, you’d want a source of water, easy transport, a relatively flat area for many buildings, and at least one high point for scenic vistas. But there was one big problem with my city plan: there were no buildings, neighborhoods, or districts on it! No buildings or people! It was just the land!

Ok, so I was in grade school, and this was one of my first projects, so perhaps I could be excused for not knowing what I was doing. But the educators who set up this project knew what they were doing, and they brought on board an actual city planner to talk to us about our project. When he saw my maps, he pointed out this wasn’t a city plan and sat down with all of us to brainstorm what we’d actually want in a city – neighborhoods, power plants, a city center, museums, libraries, hospitals, food distribution and industrial regions. At the time, I was saddened that my hard work was abandoned, and now in hindsight I’m saddened that the city planner didn’t take a minute or two to talk about how geography affects cities before beginning his brainstorming exercise. But what struck me most about this in hindsight is that I really didn’t know what constituted an answer to the problem.

So, I asked myself, “What counts as a solution to this problem?” – and that, I realized, is a very good question.

-the Centaur

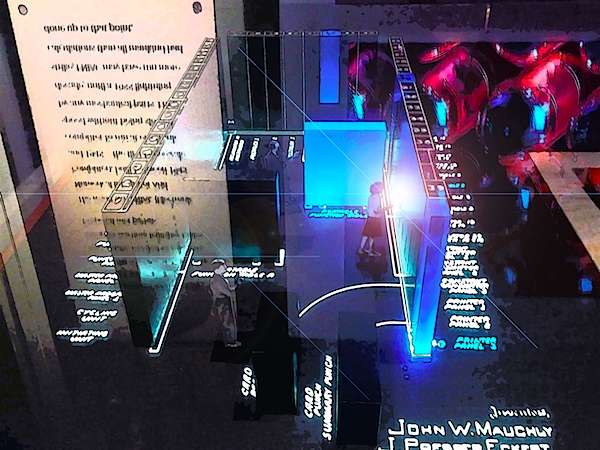

Pictured: an overhead shot of a diorama of the control room of the ENIAC computer as seen at the Computer History Museum, and of course our friend Clarence having his sudden moment of clarity.