When I was growing up - or at least when I was a young graduate student in a

Schankian research lab - we were all focused on understanding: what did it mean, scientifically speaking, for a person to understand something, and could that be recreated on a computer? We all sort of knew it was what we'd call nowadays an

ill-posed problem, but we had a good

operational definition, or at least an operational counterexample: if a computer read a story and could not answer the questions that a typical human being could answer about that story, it didn't understand it at all.

But there are at least two ways to define a word. What I'll call a practical definition is what a semanticist might call the denotation of a word: a narrow definition, one which you might find in a dictionary, which clearly specifies the meaning of the concept, like a bachelor being an unmarried man. What I'll call a philosophical definition, the connotations of a word, are the vast web of meanings around the core concept, the source of the fine sense of unrightness that one gets from describing Pope Francis as a bachelor, the nuances of meaning embedded in words that Socrates spent his time pulling out of people, before they went and killed him for being annoying.

It's those connotations of "understanding" that made all us Schankians very leery of saying our computer programs fully "understood" anything, even as we were pursuing computer understanding as our primary research goal. I care a lot about understanding, deep understanding, because, frankly, I cannot effectively do my job of teaching robots to learn if I do not deeply understand robots, learning, computers, the machinery surrounding them, and the problem I want to solve; when I do not understand all of these things, I stumble in the dark, I make mistakes, and end up sad.

And it's pursuing a deeper understanding about deep learning where I got a deeper insight into deep understanding. I was "deep reading" the

Deep Learning book (a practice in which I read, or re-read, a book I've read, working out all the equations in advance before reading the derivations), in particular section

5.8.1 on Principal Components Analysis, and the authors made the same comment I'd just seen in the

Hands-On Machine Learning book: "the mean of the samples must be zero prior to applying

PCA."

Wait, what? Why? I mean, thank you for telling me, I'll be sure to do that, but, like ...

why? I didn't follow up on that question right away, because the authors also tossed off an offhand comment like, "

X⊤X is the unbiased sample covariance matrix associated with a sample

x" and I'm like, what the hell, where did

that come from? I had recently read the section on variance and covariance but had no idea why this would be associated with the transpose

⊤ of the design matrix

X multiplied by

X itself. (In case you're new to machine learning, if

x stands for an example input to a problem, say a list of the pixels of an image represented as a column of numbers, then the design matrix

X is all the examples you have, but each example listed as a row. Perfectly not confusing? Great!)

So, since I didn't understand why

Var[x] =

X⊤X, I set out to prove it myself. (Carpenters say, measure twice, cut once, but they'd better have a heck of a lot of measuring and cutting under their belts - moreso, they'd better know when to cut and measure before they start working on your back porch, or you and they will have a bad time. Same with trying to teach robots to learn: it's more than just practice; if you don't know why something works, it will come back to bite you, sooner or later, so, dig in until you get it). And I quickly found that the "covariance matrix of a variable

x" was a thing, and quickly started to intuit that the matrix multiplication would produce it.

This is what I'd call surface level understanding: going forward from the definitions to obvious conclusions. I knew the definition of matrix multiplication, and I'd just re-read the definition of covariance matrices, so I could see these would fit together. But as I dug into the problem, it struck me: true understanding is more than just going forward from what you know: "

The brain does much more than just recollect; it inter-compares, it synthesizes, it analyzes, it generates abstractions" - thank you, Carl Sagan. But this kind of understanding is a vast, ill-posed problem - meaning, a problem without a unique and unambiguous solution.

But as I was continuing to dig through the problem, reading through the sections I'd just read on "sample estimators," I had a revelation. (Another aside: "sample estimators" use the data you have to predict data you don't, like estimating the height of males in North America from a random sample of guys across the country; "unbiased estimators" may be wrong but their errors are grouped around the true value). The formula for the unbiased sample estimator for the variance actually doesn't look quite the matrix transpose - but it depends on the unbiased estimator of sample mean.

Suddenly, I felt that I understood why PCA data had to have a mean of 0. Not driving forward from known facts and connecting their inevitable conclusions, but driving backwards from known facts to hypothesize a connection which I could explore and see. I even briefly wrote a draft of the ideas behind this essay - then set out to prove what I thought I'd seen. Setting the mean of the samples to zero made the sample mean drop out of sample variance - and then the matrix multiplication formula dropped out. Then I knew I understood why PCA data had to have a mean of 0 - or how to rework PCA to deal with data which had a nonzero mean.

This I'd call deep understanding: reasoning backwards from what we know to provide reasons for why things are the way they are. A recent book on science I read said that some regularities, like the length of the day, may be predictive, but other regularities, like the tides, cry out for explanation. And once you understand Newton's laws of motion and gravitation, the mystery of the tides is readily solved - the answer falls out of inertia, angular momentum, and gravitational gradients. With apologies to Larry Niven, of course

a species that understands gravity will be able to predict tides.

The brain does do more than just remember and predict to guide our next actions: it builds structures that help us understand the world on a deeper level, teasing out rules and regularities that help us not just plan, but strategize. Detective Benoit Blanc from the movie

Knives Out claimed to "

anticipate the terminus of gravity's rainbow" to help him solve crimes; realizing how gravity makes projectiles arc, using that to understand why the trajectory must be the observed parabola, and strolling to the target.

So I'd argue that true understanding is not just forward-deriving inferences from known rules, but also backward-deriving causes that can explain behavior. And this means computing the inverse of whatever forward prediction matrix you have, which is a more difficult and challenging problem, because that matrix may have a well-defined inverse. So true understanding is indeed a deep and interesting problem!

But, even if we teach our computers to understand this way ... I suspect that this won't exhaust what we need to understand about understanding. For example: the dictionary definitions I've looked up don't mention it, but the idea of seeking a root cause seems embedded in the word "under - standing" itself ... which makes me suspect that the other half of the word, standing, itself might hint at the stability, the reliability of the inferences we need to be able to make to truly understand anything.

I don't think we've reached that level of understanding of understanding yet.

-the Centaur

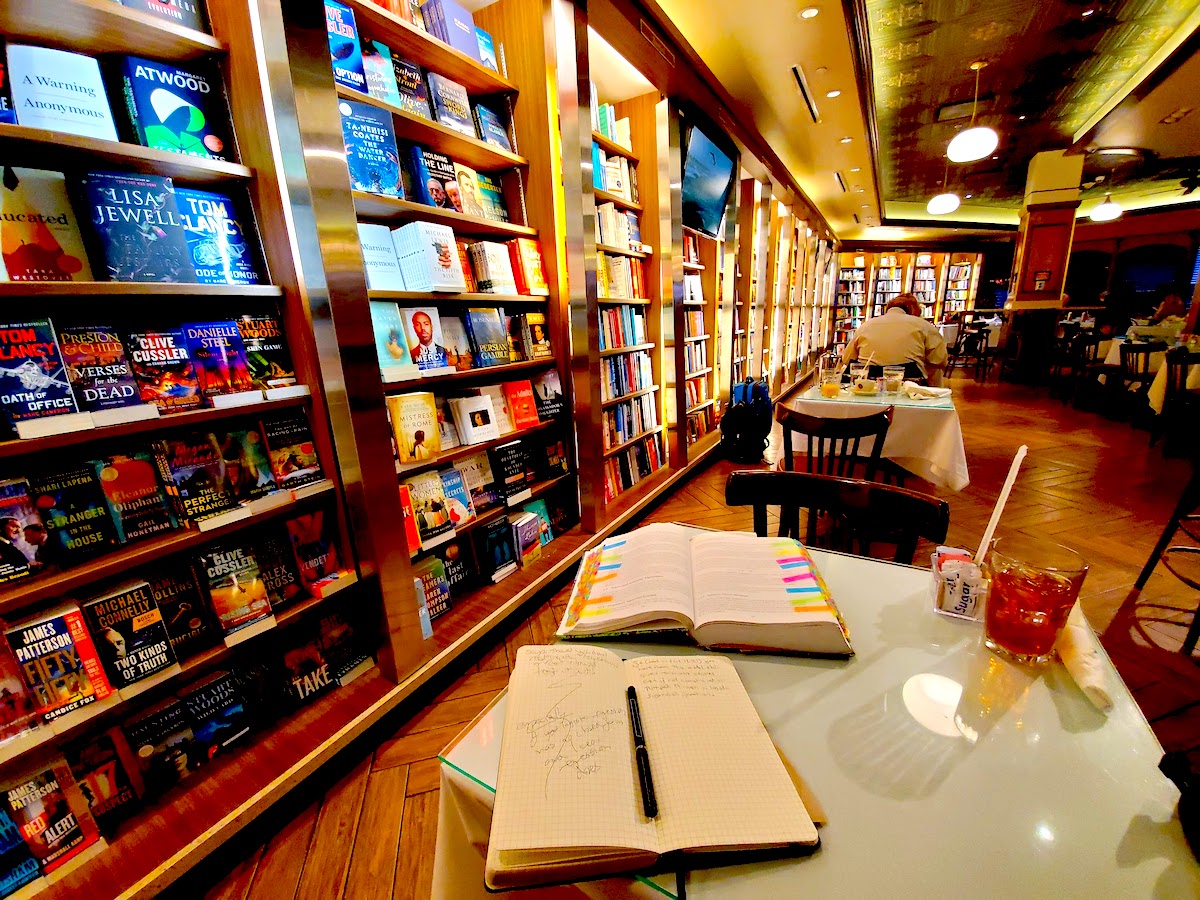

Pictured: Me working on a problem in a bookstore. Probably not this one.

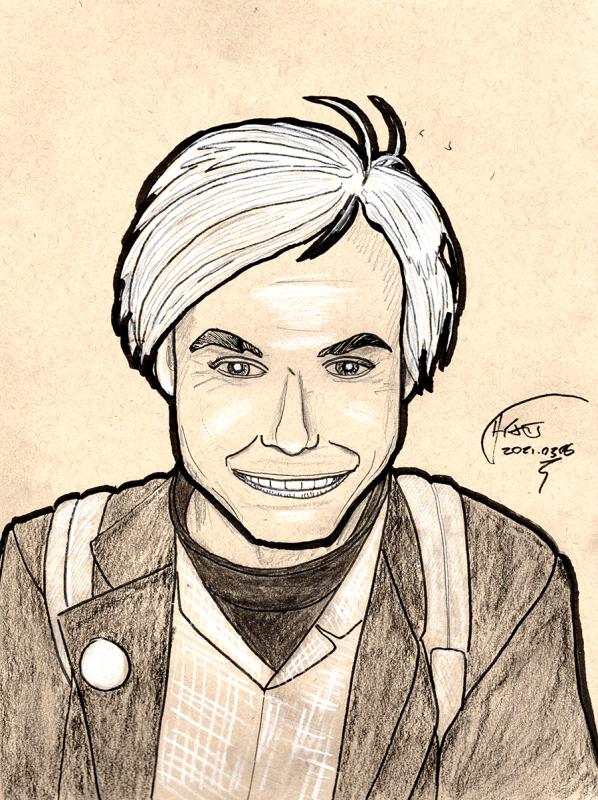

What started to a quick sketch ended up with me pulling out all the stops so I didn't have to stay up to 4:30 in the morning. Roughed with a 2B pencil on Strathmore 9x12 Toned Tan, then inked with Sakura Micron pens, with shading and white highlights with Winsor-Newton Hard, Medium and White Charcoal plus a little 2B and final outlining with a Sakura Pigma brush pen. I like doing renderings on toned paper as you can go up to white and down to dark, giving you more ways to push the drawing. The face still is too wide, and is missing something, compared to the source image (credited to Maurizio Codogno):

[caption id="attachment_5096" align="alignnone" width="600"]

What started to a quick sketch ended up with me pulling out all the stops so I didn't have to stay up to 4:30 in the morning. Roughed with a 2B pencil on Strathmore 9x12 Toned Tan, then inked with Sakura Micron pens, with shading and white highlights with Winsor-Newton Hard, Medium and White Charcoal plus a little 2B and final outlining with a Sakura Pigma brush pen. I like doing renderings on toned paper as you can go up to white and down to dark, giving you more ways to push the drawing. The face still is too wide, and is missing something, compared to the source image (credited to Maurizio Codogno):

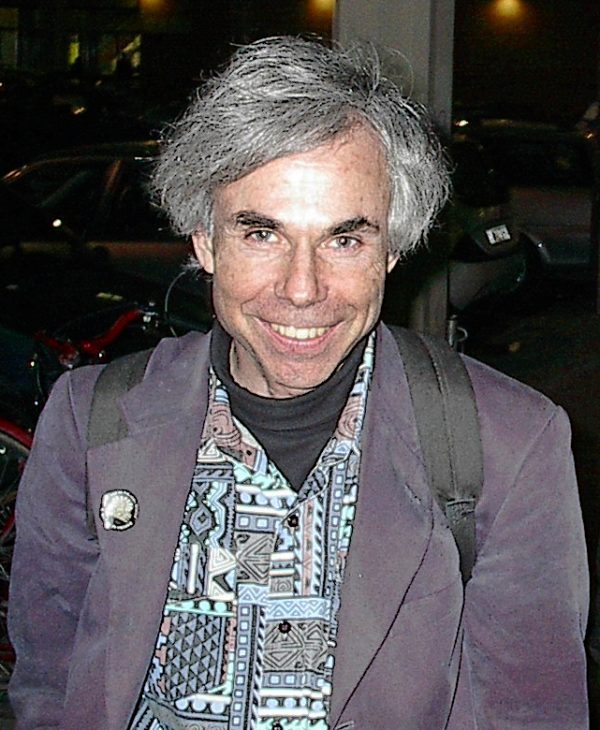

[caption id="attachment_5096" align="alignnone" width="600"] Douglas Hofstadter in Bologna, Italy - 06 March 2002[/caption]

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

Douglas Hofstadter in Bologna, Italy - 06 March 2002[/caption]

Drawing every day.

-the Centaur

So I think a lot about how to be a better scientist, and during my reading I found a sparkly little gem by one of the greatest experimentalists of all time, Michael Faraday. It's quoted in

So I think a lot about how to be a better scientist, and during my reading I found a sparkly little gem by one of the greatest experimentalists of all time, Michael Faraday. It's quoted in  Inspirational physicist Richard Feynman once said "the sole test of any idea is experiment." I prefer the formulation "the sole test of any idea open to observation is experiment," because opening our ideas to observation - rather than relying on just belief, instrumentation, or arguments - is often the hardest challenge in making progress on otherwise seemingly unresolvable problems.

-the Centaur

Inspirational physicist Richard Feynman once said "the sole test of any idea is experiment." I prefer the formulation "the sole test of any idea open to observation is experiment," because opening our ideas to observation - rather than relying on just belief, instrumentation, or arguments - is often the hardest challenge in making progress on otherwise seemingly unresolvable problems.

-the Centaur  Marriott, bottom floor, International Hall South. Follow the signs for the author signing, you can't miss it!

Marriott, bottom floor, International Hall South. Follow the signs for the author signing, you can't miss it!