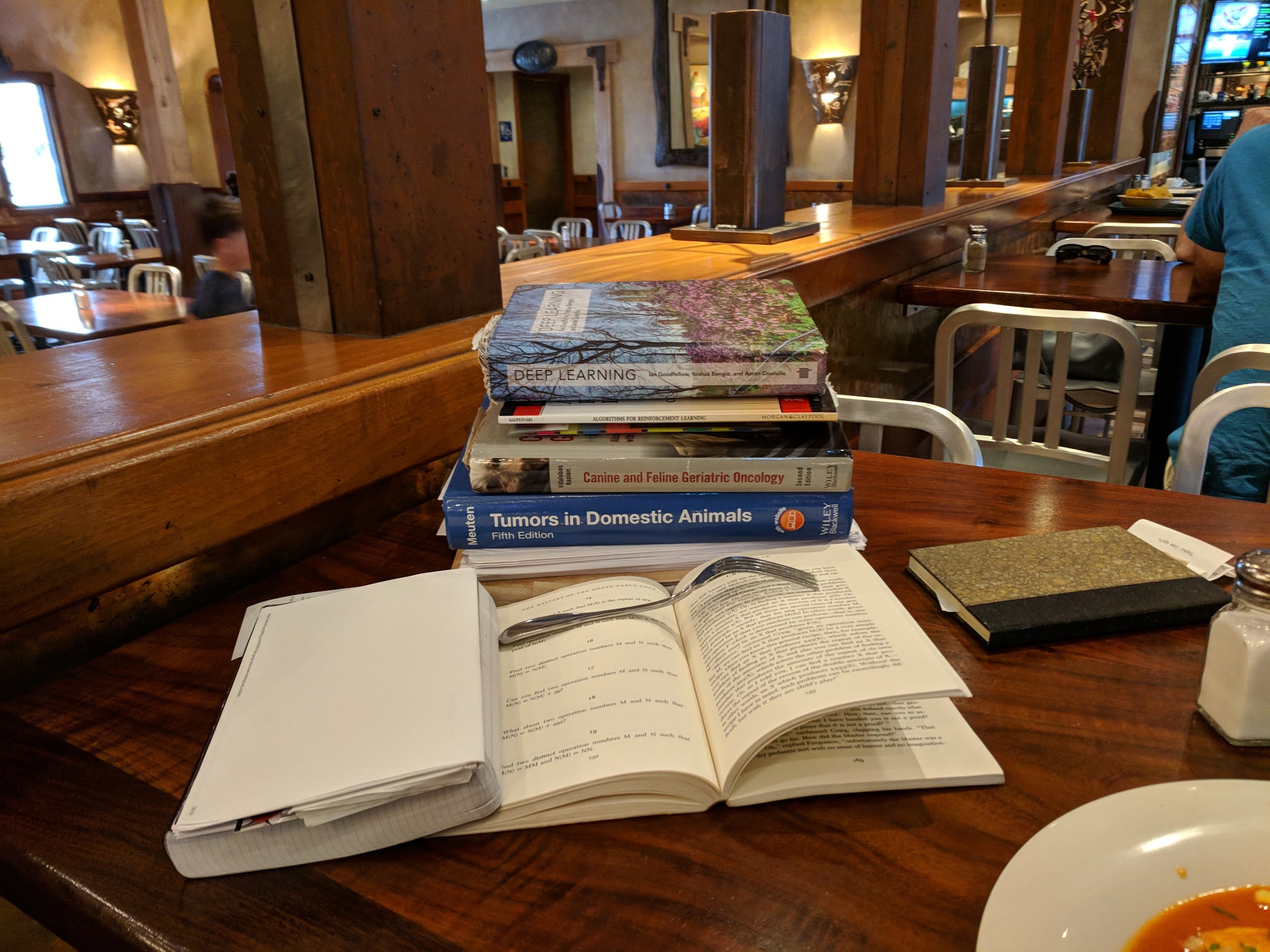

Above is what looks like a massive anthill at the border of the "lawn" and "forest" parts of our property. It's been getting bigger and bigger over the years, and that slow growth always reminds me of Mr. Morden's comments in Babylon 5 about the Shadows' plan to make lesser races fight:

JUSTIN: "It's really simple. You bring two sides together. They fight. A lot of them die, but those who survive are stronger, smarter and better."

Babylon 5: Z'ha'dum

MORDEN: "It's like knocking over an ant-hill. Every new generation gets stronger, the ant-hill gets redesigned, made better."

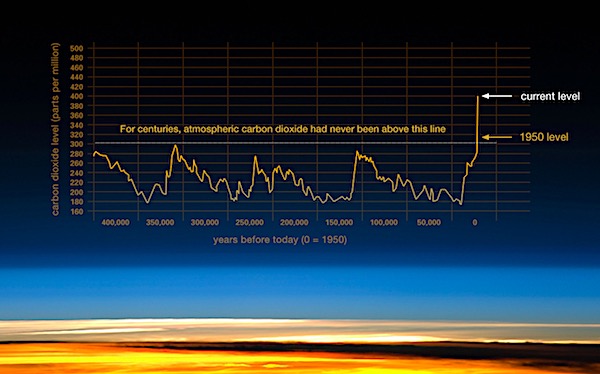

But the Shadows were wrong, and what we're seeing there isn't a redesigned anthill: it is a catastrophe, a multigenerational ant catastrophe caused by climate, itself brought to light by a larger, slow-motion human catastrophe caused by climate change.

Humans have farmed, built and burnt for a long time, but only now, in the dawn of the Anthropocene - that period of time where human impacts on climate start to exceed natural variation of climate itself, beginning roughly in the 1900s - have those effects really come back to bite us on a global, rather than local, scale.

For my wife and I, this took the form of fire. Fire was not new in California: friends who lived on homes on ridges complained about their high insurance costs as far back as I can remember. But more and more fires started burning across our area, forcing other friends to move away. Then three burned within five miles of our home, with no end to the drought in sight, and we decided we'd had enough.

We moved to my ancestral home, a place where water falls from the sky, aptly named Greenville. And we moved into a house whose builders knew about rain, and placed it on a hill with carefully designed drainage. They created great rolling lawns, manicured in the traditional Greenville "let's fucking force it with chemicals and lawnmowers to look like it was Astroturf" which we are slowly letting go back to nature.

In this grass, and in the absence of pesticides, the ants flourished. But this isn't precisely a natural environment: they're flourishing in an expanse of grass that is wider and more rounded than the rough, ridged forest around it. In the forest, runoff from the rains is channeled into proto-streams leading to the nearby creek; at the edge of the lawn, water from the house and lawn spills out in a flood.

Each heavy rain, the anthills building up in the sloped grass are washed to the mulch beds that mark the boundary of the forest, and there the ants start to re-build. But lighter rains can destroy these more exposed anthills, forcing them to slowly migrate back up into the grass. That had already happened here: that was no longer a live anthill, and unbeknownst to me, I was standing in its replacement.

No worries, for them or me; I noticed the anthill was dead, looked down, and moved off their territory just as the ants were swarming out of their antholes, fit to kill (or at least to annoyingly nibble). But the great red field there, as wide as a man is tall and twice as long, was not a functioning anthill: it was the accumulated wreckage of generation after generation of ant catastrophes.

In the quote, Mr. Morden was wrong: knocking over an anthill doesn't make it come back better designed. Justin got it a little better: the strongest and smartest do often survive a battle - but they walk away with scars, and sometimes the winners may just be the lucky ones. Conflict may not make people better - it can just leave scarred soldiers, wounded refugees and a destroyed landscape.

Now, the Shadows were the villains of the story, but every good villain needs a good soundbite that makes them sound at least a little bit good, and it's worth demolishing this one. "The anthill comes back better stronger and better designed" is designed to riff on the survival of the fittest - the notion that creating survival pressure will lead to stronger, smarter, and better individuals.

But evolution doesn't work that way. Those stronger, smarter, and better individuals have to have existed in the population in the first place. Evolution only leads to improvements over time at all if the variation of the population continues to yield increasingly better individuals generation after generation - and that is not at all guaranteed. The actual historical pattern is far closer to the opposite.

Now, people who should know better often claim that evolution has no direction. I think that's because there's a cartoon version of evolution where things tend to get more complex over time, and they want to replace it with another cartoon version of evolution which is blind and random - perhaps spillover from Dawkins' attempts to argue with creationists using his Blind Watchmaker idea.

But that's not how evolution works at all. Evolution does have a direction - just like gravity does. Only at the narrow level of the fundamental laws operating on idealized, homogeneous substrates can we say gravity is symmetric, or evolution is directionless. Once the scope of our investigation expands and the structure of the world gets complex - once symmetry is broken - then gravity clumps matter into planets and gives us "up", and evolution molds organisms into ecosystems and gives us "progress towards complexity".

But the direction of evolution is a lot more like the gradient of air around a planet than it is any kind of "great chain of being". Once an ecosystem exists, increased complexity provides an advantage for a small set of organisms, and as they spread into the ecosystem, a niche is created for even more complex organisms to exceed them. But, just like most of the atmosphere is closest to the surface of a planet, most of the organisms will remain the simplest ones.

Adding additional selection pressure won't give you more complex organisms: it will give you fewer of them. The more stress on the ecosystem, the harder it is for anything to survive, the size of the various niches will shrink, and even if the ecosystem still provides enough resources to support complex organisms, the size of the population that can evolve will drop, making it less likely for even more complex ones to arise - and that's assuming it doesn't get so rough that the complex organisms go extinct.

Eventually, atoms bouncing around in the atmosphere may fly off into space - just like, eventually, evolution produced a Neil Armstrong who flew to the moon. But pouring energy into the atmosphere may slough the upper layers off into space, leaving a thin remnant closest to the planet - and, so, stressing an ecosystem will not produce more astronauts; it may kill them off and leave everyone down in the muck.

Which gives us a hint to what the Shadows' real plan was. They're portrayed as an ancient learned race, so presumably they knew everything I just shared - but they're also portrayed as the villains, after all, and so they ultimately had a self-serving goal in mind. And if knocking over an anthill doesn't make it come back better designed, then their real goal was to keep kicking over anthills so they themselves would stay on top.

-the Centaur

Pictured: Me, near sunset, taking picture of what I thought was a live anthill - until I looked more closely.

Yeah, so that happened on my attempt to get some rest on my Sabbath day.

I'm not going to cite the book - I'm going to do the author the courtesy of re-reading the relevant passages to make sure I'm not misconstruing them, but I'm not going to wait to blog my reaction - but what caused me to throw this book, an analysis of the flaws of the scientific method, was this bit:

Imagine an experiment with two possible outcomes: the new theory (cough EINSTEIN) and the old one (cough NEWTON). Three instruments are set up. Two report numbers consistent with the new theory; the third one, missing parts, possibly configured improperly and producing noisy data, matches the old.

Wow! News flash: any responsible working scientist would say these results favored the new theory. In fact, if they were really experienced, they might have even thrown out the third instrument entirely - I've learned, based on red herrings from bad readings, that it's better not to look too closely at bad data.

What did the author say, however? Words to the effect: "The scientists ignored the results from the third instrument which disproved their theory and supported the original, and instead, pushing their agenda, wrote a paper claiming that the results of the experiment supported their idea."

Pushing an agenda? Wait, let me get this straight, Chester Chucklewhaite: we should throw out two results from well-functioning instruments that support theory A in favor of one result from an obviously messed-up instrument that support theory B - oh, hell, you're a relativity doubter, aren't you?

Chuck-toss.

I'll go back to this later, after I've read a few more sections of E. T. Jaynes's Probability Theory: The Logic of Science as an antidote.

-the Centaur

P. S. I am not saying relativity is right or wrong, friend. I'm saying the responsible interpretation of those experimental results as described would be precisely the interpretation those scientists put forward - though, in all fairness to the author of this book, the scientist involved appears to have been a super jerk.

Yeah, so that happened on my attempt to get some rest on my Sabbath day.

I'm not going to cite the book - I'm going to do the author the courtesy of re-reading the relevant passages to make sure I'm not misconstruing them, but I'm not going to wait to blog my reaction - but what caused me to throw this book, an analysis of the flaws of the scientific method, was this bit:

Imagine an experiment with two possible outcomes: the new theory (cough EINSTEIN) and the old one (cough NEWTON). Three instruments are set up. Two report numbers consistent with the new theory; the third one, missing parts, possibly configured improperly and producing noisy data, matches the old.

Wow! News flash: any responsible working scientist would say these results favored the new theory. In fact, if they were really experienced, they might have even thrown out the third instrument entirely - I've learned, based on red herrings from bad readings, that it's better not to look too closely at bad data.

What did the author say, however? Words to the effect: "The scientists ignored the results from the third instrument which disproved their theory and supported the original, and instead, pushing their agenda, wrote a paper claiming that the results of the experiment supported their idea."

Pushing an agenda? Wait, let me get this straight, Chester Chucklewhaite: we should throw out two results from well-functioning instruments that support theory A in favor of one result from an obviously messed-up instrument that support theory B - oh, hell, you're a relativity doubter, aren't you?

Chuck-toss.

I'll go back to this later, after I've read a few more sections of E. T. Jaynes's Probability Theory: The Logic of Science as an antidote.

-the Centaur

P. S. I am not saying relativity is right or wrong, friend. I'm saying the responsible interpretation of those experimental results as described would be precisely the interpretation those scientists put forward - though, in all fairness to the author of this book, the scientist involved appears to have been a super jerk.

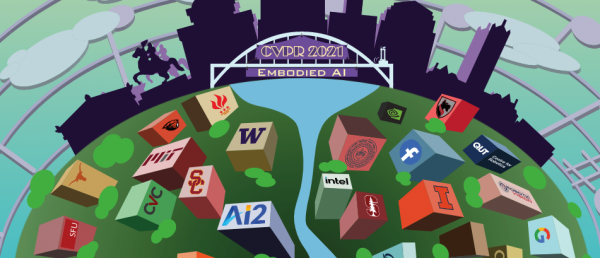

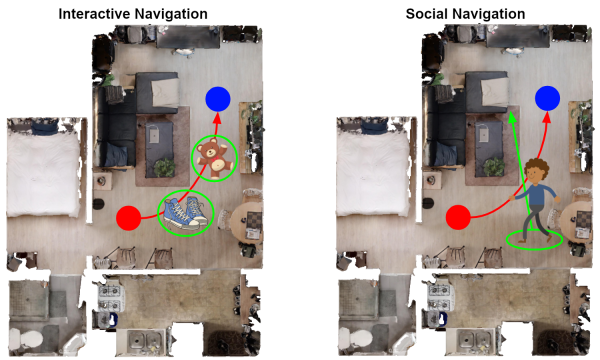

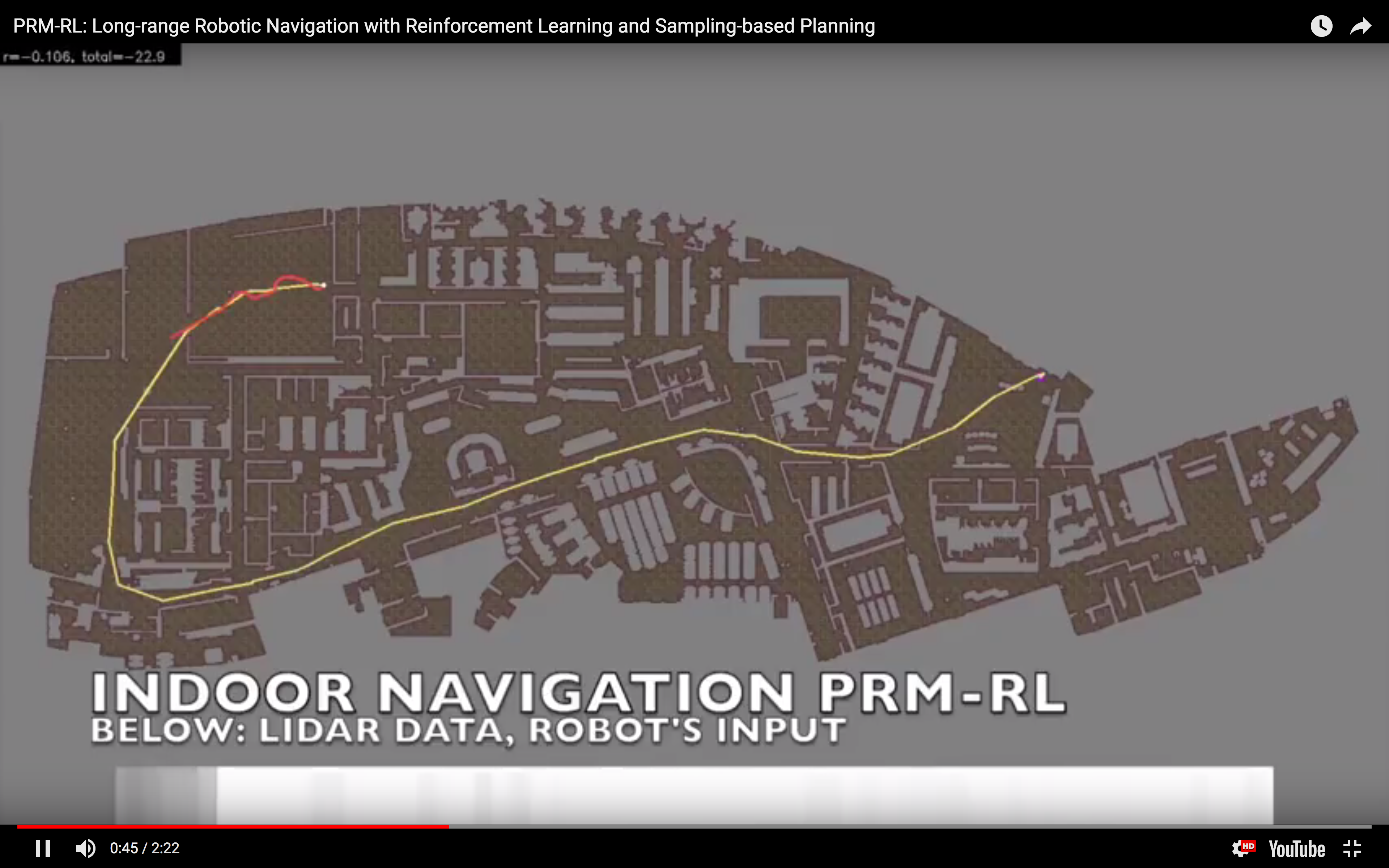

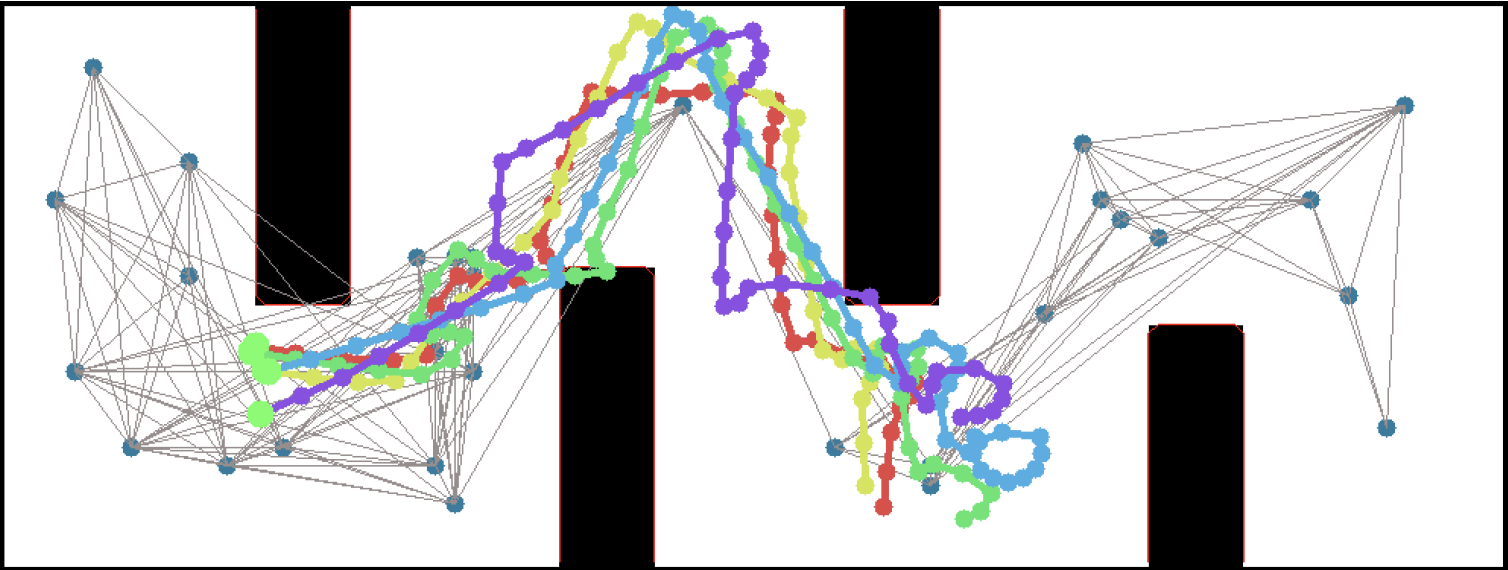

So, this happened! Our team's paper on "PRM-RL" - a way to teach robots to navigate their worlds which combines human-designed algorithms that use roadmaps with deep-learned algorithms to control the robot itself - won a best paper award at the ICRA robotics conference!

So, this happened! Our team's paper on "PRM-RL" - a way to teach robots to navigate their worlds which combines human-designed algorithms that use roadmaps with deep-learned algorithms to control the robot itself - won a best paper award at the ICRA robotics conference!

We were cited not just for this technique, but for testing it extensively in simulation and on two different kinds of robots. I want to thank everyone on the team - especially Sandra Faust for her background in PRMs and for taking point on the idea (and doing all the quadrotor work with Lydia Tapia), for Oscar Ramirez and Marek Fiser for their work on our reinforcement learning framework and simulator, for Kenneth Oslund for his heroic last-minute push to collect the indoor robot navigation data, and to our manager James for his guidance, contributions to the paper and support of our navigation work.

We were cited not just for this technique, but for testing it extensively in simulation and on two different kinds of robots. I want to thank everyone on the team - especially Sandra Faust for her background in PRMs and for taking point on the idea (and doing all the quadrotor work with Lydia Tapia), for Oscar Ramirez and Marek Fiser for their work on our reinforcement learning framework and simulator, for Kenneth Oslund for his heroic last-minute push to collect the indoor robot navigation data, and to our manager James for his guidance, contributions to the paper and support of our navigation work.

Woohoo! Thanks again everyone!

-the Centaur

Woohoo! Thanks again everyone!

-the Centaur  When I was a kid (well, a teenager) I'd read puzzle books for pure enjoyment. I'd gotten started with Martin Gardner's mathematical recreation books, but the ones I really liked were Raymond Smullyan's books of logic puzzles. I'd go to Wendy's on my lunch break at Francis Produce, with a little notepad and a book, and chew my way through a few puzzles. I'll admit I often skipped ahead if they got too hard, but I did my best most of the time.

I read more of these as an adult, moving back to the Martin Gardner books. But sometime, about twenty-five years ago (when I was in the thick of grad school) my reading needs completely overwhelmed my reading ability. I'd always carried huge stacks of books home from the library, never finishing all of them, frequently paying late fees, but there was one book in particular - The Emotions by Nico Frijda - which I finished but never followed up on.

Over the intervening years, I did finish books, but read most of them scattershot, picking up what I needed for my creative writing or scientific research. Eventually I started using the tiny little notetabs you see in some books to mark the stuff that I'd written, a "levels of processing" trick to ensure that I was mindfully reading what I wrote.

A few years ago, I admitted that wasn't enough, and consciously began trying to read ahead of what I needed to for work. I chewed through C++ manuals and planning books and was always rewarded a few months later when I'd already read what I needed to to solve my problems. I began focusing on fewer books in depth, finishing more books than I had in years.

Even that wasn't enough, and I began - at last - the re-reading project I'd hoped to do with The Emotions. Recently I did that with Dedekind's Essays on the Theory of Numbers, but now I'm doing it with the Deep Learning. But some of that math is frickin' beyond where I am now, man. Maybe one day I'll get it, but sometimes I've spent weeks tackling a problem I just couldn't get.

Enter puzzles. As it turns out, it's really useful for a scientist to also be a science fiction writer who writes stories about a teenaged mathematical genius! I've had to simulate Cinnamon Frost's staggering intellect for the purpose of writing the Dakota Frost stories, but the further I go, the more I want her to be doing real math. How did I get into math? Puzzles!

So I gave her puzzles. And I decided to return to my old puzzle books, some of the ones I got later but never fully finished, and to give them the deep reading treatment. It's going much slower than I like - I find myself falling victim to the "rule of threes" (you can do a third of what you want to do, often in three times as much time as you expect) - but then I noticed something interesting.

Some of Smullyan's books in particular are thinly disguised math books. In some parts, they're even the same math I have to tackle in my own work. But unlike the other books, these problems are designed to be solved, rather than a reflection of some chunk of reality which may be stubborn; and unlike the other books, these have solutions along with each problem.

So, I've been solving puzzles ... with careful note of how I have been failing to solve puzzles. I've hinted at this before, but understanding how you, personally, usually fail is a powerful technique for debugging your own stuck points. I get sloppy, I drop terms from equations, I misunderstand conditions, I overcomplicate solutions, I grind against problems where I should ask for help, I rabbithole on analytical exploration, and I always underestimate the time it will take for me to make the most basic progress.

Know your weaknesses. Then you can work those weak mental muscles, or work around them to build complementary strengths - the way Richard Feynman would always check over an equation when he was done, looking for those places where he had flipped a sign.

Back to work!

-the Centaur

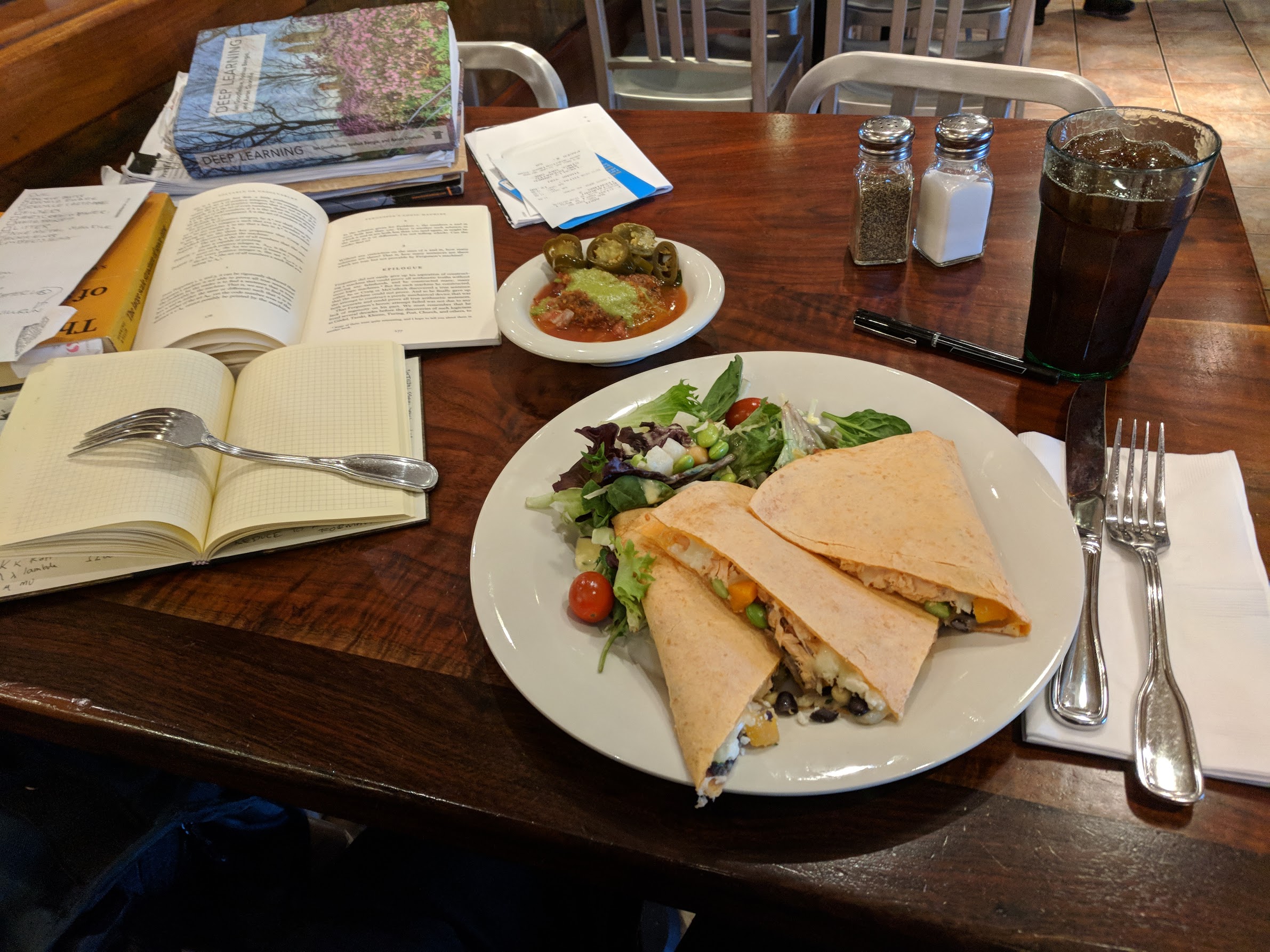

Pictured: my "stack" at a typical lunch. I'll usually get to one out of three of the things I bring for myself to do. Never can predict which one though.

When I was a kid (well, a teenager) I'd read puzzle books for pure enjoyment. I'd gotten started with Martin Gardner's mathematical recreation books, but the ones I really liked were Raymond Smullyan's books of logic puzzles. I'd go to Wendy's on my lunch break at Francis Produce, with a little notepad and a book, and chew my way through a few puzzles. I'll admit I often skipped ahead if they got too hard, but I did my best most of the time.

I read more of these as an adult, moving back to the Martin Gardner books. But sometime, about twenty-five years ago (when I was in the thick of grad school) my reading needs completely overwhelmed my reading ability. I'd always carried huge stacks of books home from the library, never finishing all of them, frequently paying late fees, but there was one book in particular - The Emotions by Nico Frijda - which I finished but never followed up on.

Over the intervening years, I did finish books, but read most of them scattershot, picking up what I needed for my creative writing or scientific research. Eventually I started using the tiny little notetabs you see in some books to mark the stuff that I'd written, a "levels of processing" trick to ensure that I was mindfully reading what I wrote.

A few years ago, I admitted that wasn't enough, and consciously began trying to read ahead of what I needed to for work. I chewed through C++ manuals and planning books and was always rewarded a few months later when I'd already read what I needed to to solve my problems. I began focusing on fewer books in depth, finishing more books than I had in years.

Even that wasn't enough, and I began - at last - the re-reading project I'd hoped to do with The Emotions. Recently I did that with Dedekind's Essays on the Theory of Numbers, but now I'm doing it with the Deep Learning. But some of that math is frickin' beyond where I am now, man. Maybe one day I'll get it, but sometimes I've spent weeks tackling a problem I just couldn't get.

Enter puzzles. As it turns out, it's really useful for a scientist to also be a science fiction writer who writes stories about a teenaged mathematical genius! I've had to simulate Cinnamon Frost's staggering intellect for the purpose of writing the Dakota Frost stories, but the further I go, the more I want her to be doing real math. How did I get into math? Puzzles!

So I gave her puzzles. And I decided to return to my old puzzle books, some of the ones I got later but never fully finished, and to give them the deep reading treatment. It's going much slower than I like - I find myself falling victim to the "rule of threes" (you can do a third of what you want to do, often in three times as much time as you expect) - but then I noticed something interesting.

Some of Smullyan's books in particular are thinly disguised math books. In some parts, they're even the same math I have to tackle in my own work. But unlike the other books, these problems are designed to be solved, rather than a reflection of some chunk of reality which may be stubborn; and unlike the other books, these have solutions along with each problem.

So, I've been solving puzzles ... with careful note of how I have been failing to solve puzzles. I've hinted at this before, but understanding how you, personally, usually fail is a powerful technique for debugging your own stuck points. I get sloppy, I drop terms from equations, I misunderstand conditions, I overcomplicate solutions, I grind against problems where I should ask for help, I rabbithole on analytical exploration, and I always underestimate the time it will take for me to make the most basic progress.

Know your weaknesses. Then you can work those weak mental muscles, or work around them to build complementary strengths - the way Richard Feynman would always check over an equation when he was done, looking for those places where he had flipped a sign.

Back to work!

-the Centaur

Pictured: my "stack" at a typical lunch. I'll usually get to one out of three of the things I bring for myself to do. Never can predict which one though.

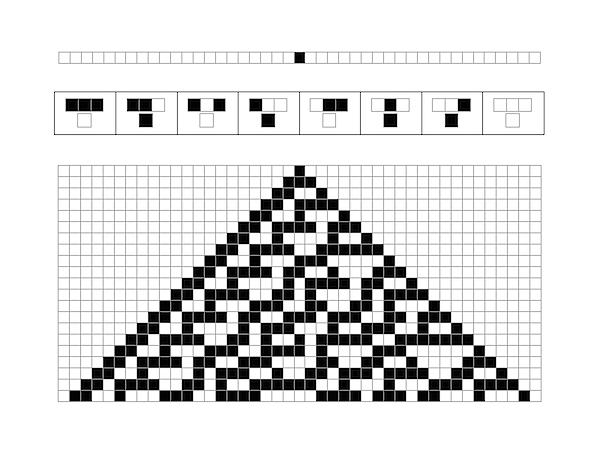

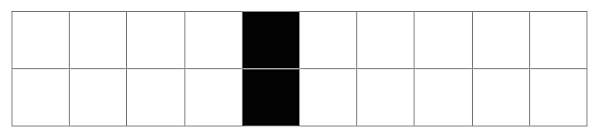

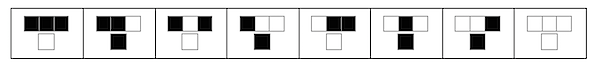

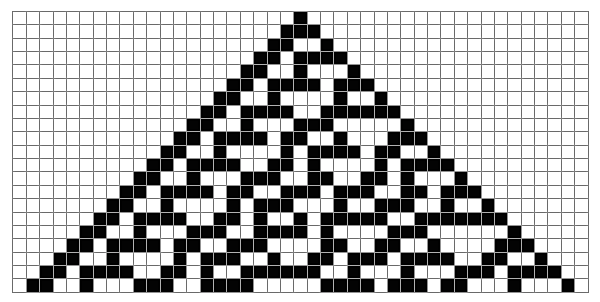

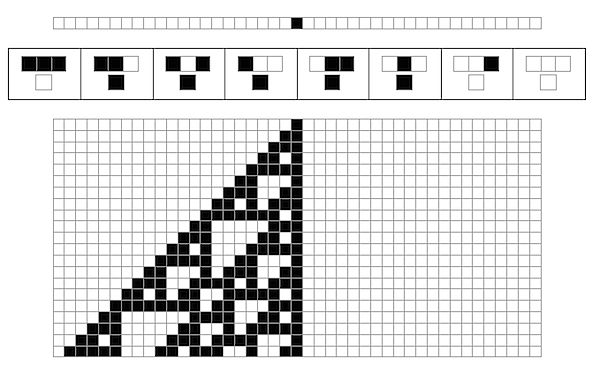

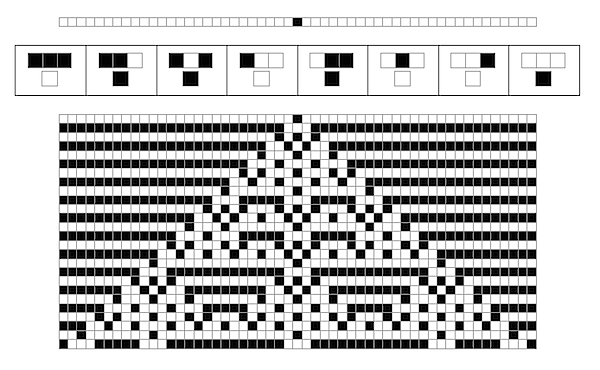

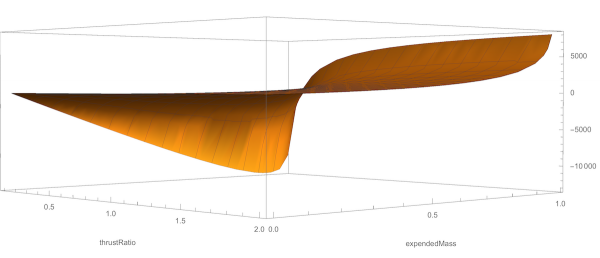

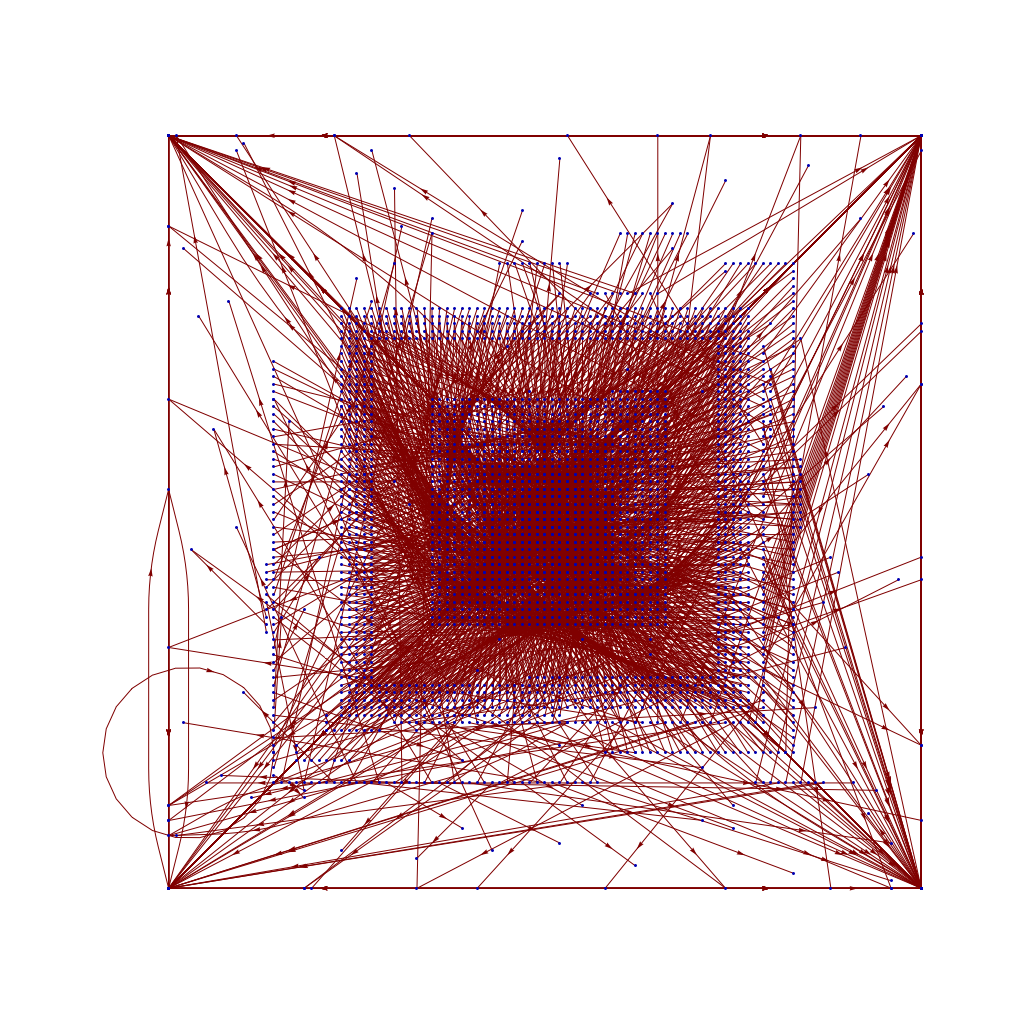

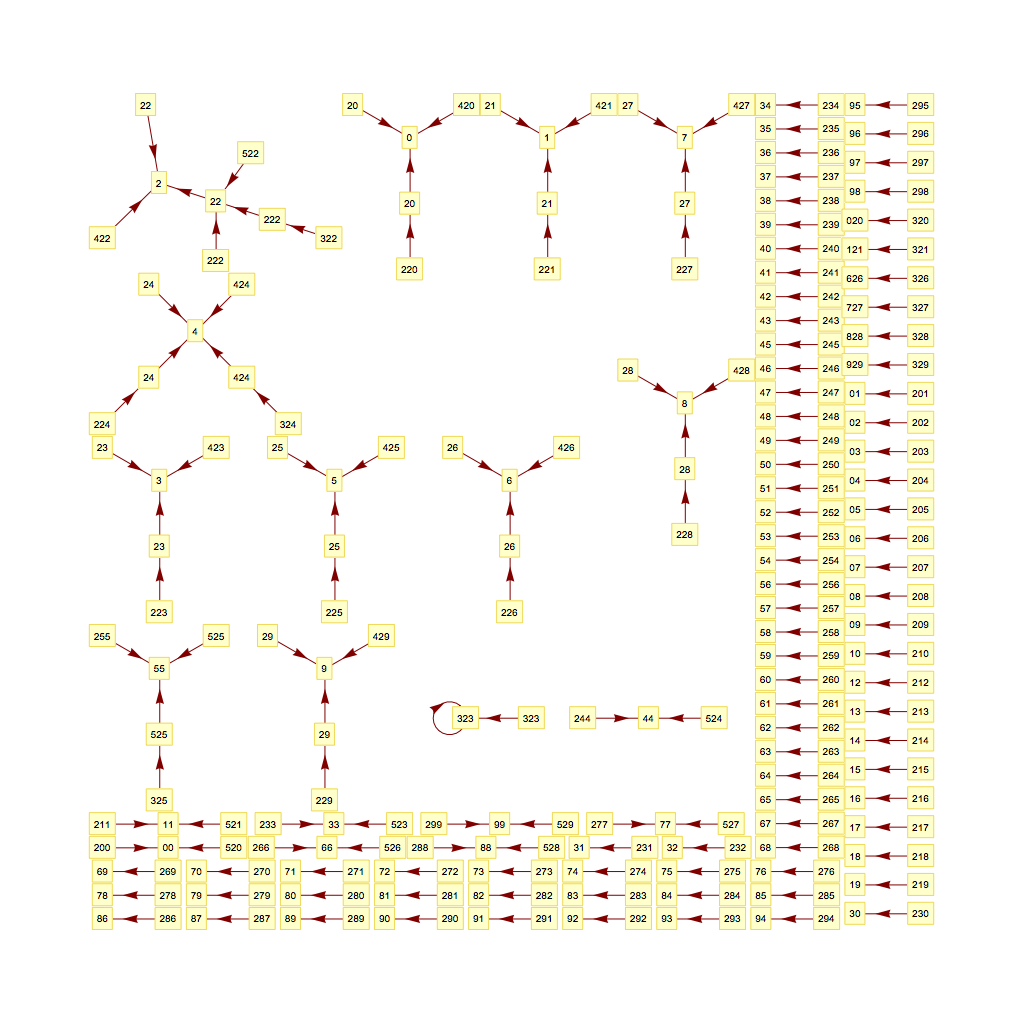

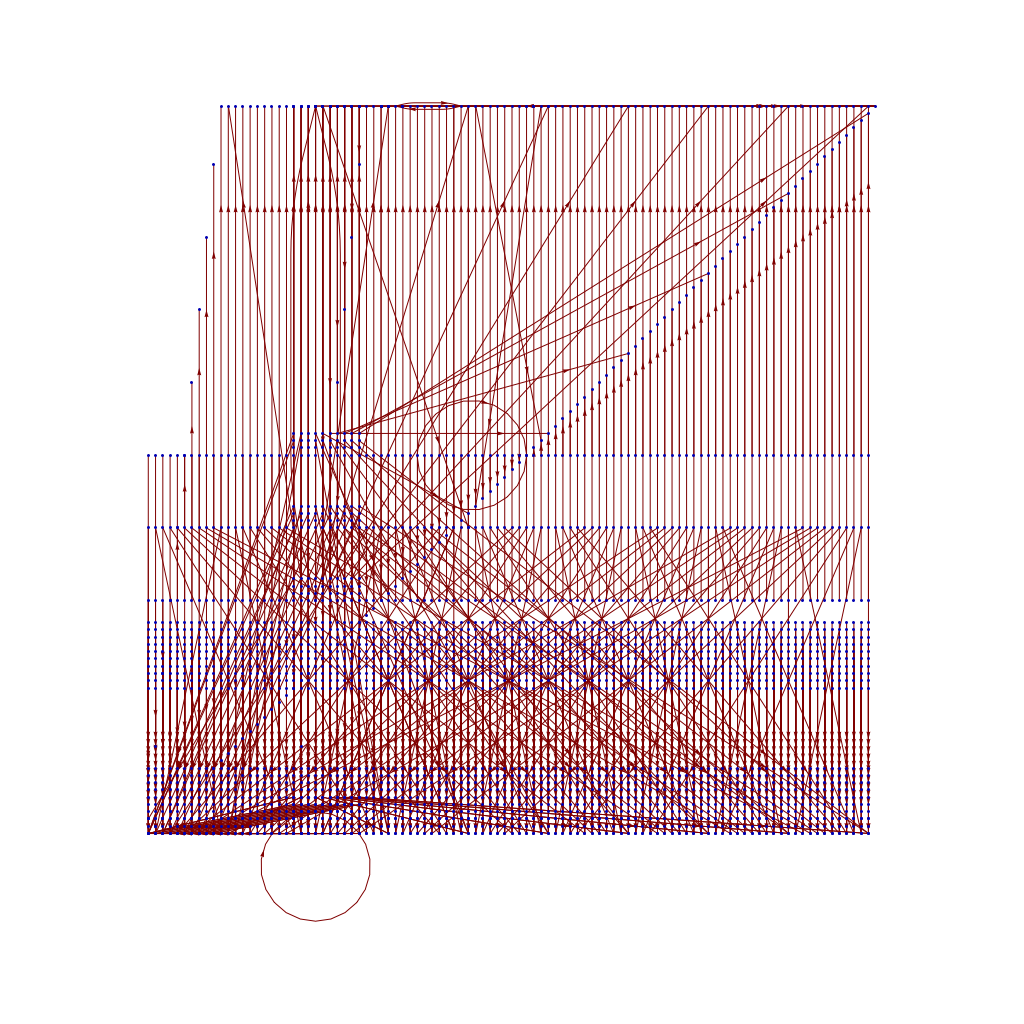

SO! There I was, trying to solve the mysteries of the universe, learn about deep learning, and teach myself enough puzzle logic to create credible puzzles for the Cinnamon Frost books, and I find myself debugging the fine details of a visualization system I've developed in Mathematica to analyze the distribution of problems in an odd middle chapter of Raymond Smullyan's

SO! There I was, trying to solve the mysteries of the universe, learn about deep learning, and teach myself enough puzzle logic to create credible puzzles for the Cinnamon Frost books, and I find myself debugging the fine details of a visualization system I've developed in Mathematica to analyze the distribution of problems in an odd middle chapter of Raymond Smullyan's  I meant well! Really I did. I was going to write a post about how finding a solution is just a little bit harder than you normally think, and how insight sometimes comes after letting things sit.

I meant well! Really I did. I was going to write a post about how finding a solution is just a little bit harder than you normally think, and how insight sometimes comes after letting things sit.

But the tools I was creating didn't do what I wanted, so I went deeper and deeper down the rabbit hole trying to visualize them.

But the tools I was creating didn't do what I wanted, so I went deeper and deeper down the rabbit hole trying to visualize them.

The short answer seems to be that there's no "there" there and that further pursuit of this sub-problem will take me further and further away from the real problem: writing great puzzles!

The short answer seems to be that there's no "there" there and that further pursuit of this sub-problem will take me further and further away from the real problem: writing great puzzles!

I often say "I teach robots to learn," but what does that mean, exactly? Well, now that one of the projects that I've worked on has been announced - and I mean, not just on

I often say "I teach robots to learn," but what does that mean, exactly? Well, now that one of the projects that I've worked on has been announced - and I mean, not just on  This work includes both our group working on office robot navigation - including Alexandra Faust, Oscar Ramirez, Marek Fiser, Kenneth Oslund, me, and James Davidson - and Alexandra's collaborator Lydia Tapia, with whom she worked on the aerial navigation also reported in the paper. Until the ICRA version comes out, you can find the preliminary version on arXiv:

This work includes both our group working on office robot navigation - including Alexandra Faust, Oscar Ramirez, Marek Fiser, Kenneth Oslund, me, and James Davidson - and Alexandra's collaborator Lydia Tapia, with whom she worked on the aerial navigation also reported in the paper. Until the ICRA version comes out, you can find the preliminary version on arXiv:

Wow. After nearly 21 years, my first published short story, “Sibling Rivalry”, is returning to print. Originally an experiment to try out an idea I wanted to use for a longer novel, ALGORITHMIC MURDER, I quickly found that I’d caught a live wire with “Sibling Rivalry”, which was my first sale to The Leading Edge magazine back in 1995.

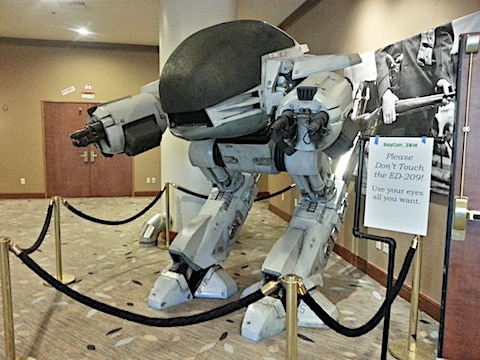

“Sibling Rivalry” was borne of frustrations I had as a graduate student in artificial intelligence (AI) watching shows like Star Trek which Captain Kirk talks a computer to death. No-one talks anyone to death outside of a Hannibal Lecter movie or a bad comic book, much less in real life, and there’s no reason to believe feeding a paradox to an AI will make it explode.

But there are ways to beat one, depending on how they’re constructed - and the more you know about them, the more potential routes there are for attack. That doesn’t mean you’ll win, of course, but … if you want to know, you’ll have to wait for the story to come out.

“Sibling Rivalry” will be the second book in Thinking Ink Press's Snapbook line, with another awesome cover by my wife Sandi Billingsley, interior design by Betsy Miller and comments by my friends Jim Davies and Kenny Moorman, the latter of whom uses “Sibling Rivalry” to teach AI in his college courses. Wow! I’m honored.

Our preview release will be at the

Wow. After nearly 21 years, my first published short story, “Sibling Rivalry”, is returning to print. Originally an experiment to try out an idea I wanted to use for a longer novel, ALGORITHMIC MURDER, I quickly found that I’d caught a live wire with “Sibling Rivalry”, which was my first sale to The Leading Edge magazine back in 1995.

“Sibling Rivalry” was borne of frustrations I had as a graduate student in artificial intelligence (AI) watching shows like Star Trek which Captain Kirk talks a computer to death. No-one talks anyone to death outside of a Hannibal Lecter movie or a bad comic book, much less in real life, and there’s no reason to believe feeding a paradox to an AI will make it explode.

But there are ways to beat one, depending on how they’re constructed - and the more you know about them, the more potential routes there are for attack. That doesn’t mean you’ll win, of course, but … if you want to know, you’ll have to wait for the story to come out.

“Sibling Rivalry” will be the second book in Thinking Ink Press's Snapbook line, with another awesome cover by my wife Sandi Billingsley, interior design by Betsy Miller and comments by my friends Jim Davies and Kenny Moorman, the latter of whom uses “Sibling Rivalry” to teach AI in his college courses. Wow! I’m honored.

Our preview release will be at the