Too Diplomatic for My Own Good

I recently watched Ridley Scott's Prometheus. I wanted to love it, and ultimately didn't, but this isn't a post about how smart characters doing dumb things to advance a plot can destroy my appreciation of a movie. Prometheus is a spiritual prequel to Alien, my second favorite movie of all time, and Alien's characters often had similar afflictions, including numerous violations of the First Rule of Horror Movies: "Don't Go Down a Dark Passageway Where No One Can Hear You if You Call For Help". Prometheus is a big, smart movie filled with grand ideas, beautiful imagery, grotesque monsters and terrifying scares. If I'd seen it before seeing a sequence of movies like Alien maybe I would have cut it more slack.

I could also critique its scientific accuracy, but I'm not going to do that. Prometheus is a space opera: very early on in the movie we see a starship boldly plying its way through the deeps, rockets blazing as it shoots towards its distant destination. If you know a lot of science, that's a big waving flag that says "don't take the science in this movie too seriously." If you want hard science, go see Avatar. Yes, I know it's a mystical tale featuring giant blue people, but the furniture of the movie --- the spaceship, the base, the equipment they use --- is so well thought out it could have been taken from Hal Clement. Even concepts like the rock-lifting "flux tube," while highly exaggerated, are based on real scientific ideas. Prometheus is not Avatar. Prometheus is like a darker cousin to Star Trek: you know, the scary cousin from the other branch you only see at the family Halloween party, the one that occasionally forgets to take his medication. He may have flunked college physics, but he can sure spin a hell of a ghost story.

What I want to do is hold up Prometheus as a bad example of how to do science. I'm not saying Ridley Scott or the screenwriters don't know science, or even that they didn't think of or even film sequences which showed more science, sequences that unfortunately ended up on the cutting room floor --- and with that I'm going to shelve my caveats. What I'm saying is that the released version of Prometheus presents a set of characters who are really poor scientists, and to show just how bad they are I'd like to compare them with the scientists in the 2011 version of The Thing, who, in contrast, do everything just about right.

But Wait ... What's a "Scientist"?

Good question. You can define them by what they do, which I'm going to try to do with this article.

But one thing scientists do is share their preliminary results with their colleagues to smoke out errors before they submit work for publication. While I make a living twiddling bits and juggling words, I was trained as (and still fancy myself as) a scientist, so I shared an early version of this essay with colleagues also trained as a scientist --- and one of them, a good friend, pointed out that there's a whole spectrum of real life scientists, from the careful to the irresponsible to the insane.

He noted "there's the platonic ideal of the Scientist, there's real-life science with its dirty little secrets, and then there's Hollywood science which is often and regrettably neither one of the previous two." So, to be clear, what I'm talking when I say scientist is the ideal scientist, Scientist-with-a-Capital-S, who does science the right way.

But to understand how the two groups of scientists in the two movies operate ... I'm going to have to spoil their plots.

Shh ... Spoilers

SPOILERS follow. If you don't want to know the plots of Prometheus and The Thing, stop reading as there are SPOILERS.

Both Prometheus and The Thing are "prequels" to classic horror movies, but the similarities don't stop there: both are stories about scientific expeditions to a remote place to study alien artifacts that prove unexpectedly dangerous when virulent, mutagenic alien life is found among the ruins. The Thing even begins with a tractor plowing through snow towards a mysterious, haunting signal, a shot which makes the tractor and its track look like a space probe rocketing towards its target --- a shot directly paralleling the early scenes of Prometheus that I mentioned earlier.

Both expeditions launch in secrecy, understandably concerned someone might "scoop" the discovery, and so both feature scientists "thrown off the deep end" with a problem. Because they're both horror movies challenging humans with existential threats, and not quasi-documentaries about how science might really work, both groups of scientists must first practice science in a "normal" mode, dealing with the expectedly unexpected, and then must shift to "abnormal" mode, dealing with unknown unknowns. "Normal" and "abnormal" science are my own definitions for the purpose of this article, to denote the two different modes in which science seems to get done in oh so many science fiction and horror movies --- science in the lab, and science when running screaming from the monster. However, as I'll explain later, even though abnormal science seems like a feature of horror movies, it's actually something that real scientists actually have a lot of experience with in the real world.

But even before the scientists in Prometheus shift to "abnormal" mode --- heck, even before they get to "normal" mode --- they go off the rails: first in how they picked the project in the first place, and second, in how they picked their team.

Why Scientists Pick Projects

You may believe Earth's Moon is made of cheese, but you're unlikely to convince NASA to dump millions into an expedition to verify your claims. Pictures of a swiss cheese wheel compared with the Moon's pockmarked surface won't get you there. Detailed mathematical models showing the correlations between the distribution of craters and cheese holes are still not likely to get you a probe atop a rocket; at best you'll get some polite smiles, because that hypothesis contradicts what we already know about the lunar surface. If, on the other hand, you cough up a spectrograph reading showing fragments of casein protein spread across the lunar surface, side by side with replication by an independent lab --- well, get packing, you're going to the Moon. What I'm getting at is that scientists are selective in picking projects --- and the more expensive the project, the more selective they get.

In one sense, science is the search for the truth, but if we look at the history of science, it isn't about proving the correctness of just any old idea: ideas are a dime a dozen. Science isn't about validating random speculations sparked by why different things look similar - for every alignment between the shoreline of Africa and South America that leads to a discovery like plate tectonics, there's a spurious match between the shape of the Pacific and the shape of the Moon that leads nowhere. (Believe it or not, this theory, which sounds ridiculous to us now, was a serious contender for the origin of the Moon many years, first proposed in 1881 by Osmond Fisher). Science is about following leads --- real evidence that leads to testable predictions, like not just a shape match between continents, but actual rock formations which are mirrored, down to their layering and fossils.

There's some subtlety to this. Nearly everybody who's not a scientist thinks that science is about finding evidence that confirms our ideas. Unfortunately, that's wrong: humans are spectacularly good at latching on evidence that confirms our ideas and spectacularly bad at picking up on evidence that disconfirms them. So we teach budding scientists in school that the scientific method depends on finding disconfirming evidence that proves bad ideas wrong. But experienced scientists funding expeditions follow follow precisely the opposite principle, at least at first: we need to find initial evidence that supports a speculation before we follow it up by looking for disconfirming evidence.

That's not to say an individual scientist can't test out even a wild and crazy idea, but even an individual scientist only has one life. In practice, we want to spend our limited resources on likely bets. For example, Einstein spent the entire latter half of his life trying to unify gravitation and quantum mechanics, but he'd probably have been better off spending a decade each on three problems rather than spending thirty years in complete failure. When it gets to a scientific expedition with millions invested and lives on the line, the effect is more pronounced. We can't simply follow every idea: we need good leads.

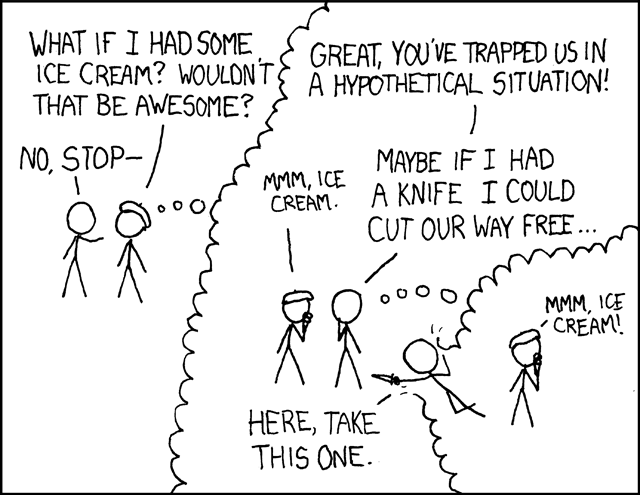

Prometheus fails this test, at least in part. The scientists begin with a good lead: in a series of ancient human cultures, none of whom have had prior contact, they find almost identical pictures, all of which depict an odd tall creature pointing to a specific constellation in the sky not visible without a telescope, a constellation with a star harboring an Earthlike planet. As leads go, that's pretty good: better than mathematical mappings between Swiss cheese holes and lunar crater sizes, but not quite as good as a spectrograph reading. It's clearly worth conducting astronomical studies or sending a probe to learn more.

But where the scientists fail is they launch a trillion dollar expedition to investigate this distant planet, an expedition which, we learn later, was actually bankrolled not because of the good lead but because of a speculation by Elizabeth, one of the paleontologists, that the tall figure in the ancient illustration is an "Engineer" who is responsible for engineering humanity, thousands of years ago. This speculation is firmly back in the lunar cheese realm because, as one character points out, it contradicts an enormous amount of biological evidence. What makes it worse is that Elizabeth has no mathematical model or analogy or even myth to point to on why she believes it: she says she simply chooses to believe it.

If I was funding the Prometheus expedition, I'd have to ask: why? Simply saying she later proves to be right is no answer: right answers reached the wrong way still aren't good science. Simply saying she has faith is not an answer; that explains why she continues to hold the belief, but not how she formed it in the first place. Or, more accurately, how she justified her belief: as one of of my colleagues reading this article pointed out, it really doesn't matter why she came to believe it, only how she came to support it. After all, the chemist Kekulé supposedly figured out benzene's ring shape after dreaming about a snake biting its tail --- but he had a lot of accumulated evidence to support that idea once he had it. So, what evidence led Elizabeth to believe that her intuition was correct?

Was there some feature of the target planet that makes it look like it is the origin of life on Earth? No, from the descriptions, it doesn't seem Earthlike enough. Was there some feature of the rock painting that makes the tall figures seem like they created humans? No, the figure looks more like a herald. So what sparked this idea in her? We just don't know. If there was some myth or inscription or pictogram or message or signal or sign or spectrogram or artifact that hinted in that direction, we could understand the genesis of her big idea, but she doesn't tell us, even though she's directly asked, and has more than enough time to say why using at least one of those words. Instead, because the filmmakers are playing with big questions without really understanding how those kinds of questions are asked or answered, she just says it's what she chooses to believe.

But that's not a good reason to fund a trillion dollar scientific expedition. Too many people choose to believe too many things for us to send spacecraft to every distant star that someone happens to wish upon --- we simply don't have enough scientists, much less trillions. If you want to spend a trillion dollars on your own idea, of course, please knock yourself out.

Now, if we didn't know the whole story of the movie, we could cut them slack based on their other scientific lead, and I'll do so because I'm not trying to bash the movie, but to bash the scientists that it depicts. And while for the rest of this article I'm going to be comparing

Prometheus with

The Thing, that isn't fair in this case. The team from

Prometheus follows up a scientific lead for a combination of reasons, one pretty good, one pretty bad. The team from

The Thing finds a

fricking alien spacecraft, or, if you want to roll it back further, they find an

unexplained radio signal in the middle of a desert which has been dead for millions of years and virtually uninhabited by humans in its whole history. This is one major non-parallel between the two movies: unlike the scientists of

Prometheus, who had to work hard for their meager scraps of leads, the scientists in

The Thing had their discovery handed to them on a silver platter.

How Scientists Pick Teams

Science is an organized body of knowledge based on the collection and analysis of data, but it isn't just the product of any old data collection and analysis: it's based on a method, a method which is based on analyzing empirical data objectively in a way which can be readily duplicated by others. Science is subtle and hard to get right. Even smart, educated, well-meaning people can fool themselves, so it's important for the people doing it to be well trained so that common mistakes in evidence collection and reasoning can be avoided.

Both movies begin with real research to establish the scientific credibility of the investigators. Early in Prometheus, the scientists Elizabeth and Charlie are shown at an archaeological dig, and later the android David practices some very real linguistics --- studying Schleicher's Fable, a highly speculative but non-fictional attempt to reconstruct early human languages --- to prepare for a possible meeting with the Engineers that Elizabeth and Charlie believe they've found. Early in The Thing, Edvard's team is shown carefully following up on a spurious radio signal found near their site, and the paleontologist Kate uses an endoscope to inspect the interior of a specimen extracted from pack ice (just to be clear, one not related to Edvard's discovery).

But in Prometheus, things almost immediately begin to go wrong. The team which made the initial discovery is marginalized, and the expedition to study their results is run by a corporate executive, Meredith, who selects a crew based on personal loyalty or willingness to accept hazard pay. Later, we find there are good reasons why Meredith picked who she did --- within the movie's logic, well worth the trillion dollars her company spent bankrolling the expedition --- but those criteria aren't scientific, and they produce an uninformed, disorganized crew whose expedition certainly explores a new world, but doesn't really do science.

The lead scientist of The Thing, Edvard, in contrast, is a scientist in charge of a substantial team on a mission of its own when he makes the discovery that starts the movie. He studies it carefully before calling in help, and when he does call in help, he calls in a close friend --- Sander, a dedicated scientist in his own right, so world-renowned that Kate recognizes him on sight. He in turn selects Kate based on another personal recommendation, because he's trying to select a team of high caliber. Sander clashes with Kate when she questions his judgment, but these are just disagreements and don't lead to foul consequences.

In short, The Thing picks scientists to do science, and this difference from Prometheus shows up almost immediately in how they choose to attack their problems.

Why Scientists Don't Bungee Jump Into Random Volcanoes

Normal science is the study of things that aren't unexpectedly trying to kill you. There may be a hazardous environment, like radiation or vacuum or political unrest, and your subject itself might be able to kill you, like a virus or a bear or a volcano, but in normal science, you know all this going in, and can take adequate precaution. Scaredycats who aren't willing to study radioactive bears on the surface of Mount Explodo while dodging the rebel soldiers of Remotistan should just stay home and do something safe, like simulate bear populations on their laptops using Mathematica. The rest of us know the risks.

Because risk is known, it's important to do science the right way. To collect data not just for the purposes of collecting it, but to do so in context. If I've seen a dozen bees today, what conclusions can you draw? Nothing. You don't know if I'm in a jungle or a desert or even if I'm a beekeeper. Even if I told you I was a beekeeper and I'd just visited a hive, you don't even know if a dozen bees is a low number, a high number, or totally unexpected. Is it a new hive just getting started, or an old hive dying out? Is it summer or winter? Did I record at noon or midnight? Was I counting inside or outside the hive? Even if you knew all that, you can interpret the number better if you know the recent and typical statistics for beehives in that region, plus maybe the weather, plus ...

What I'm getting at that it does you no good as a scientist to bungee jump into random volcanoes to snap pictures of bubbling lava, no matter how photogenic that looks on the cover of National Geographic or Scientific American. Science works when we record observations in context, so we can organize the data appropriately and develop models of its patterns, explanations of its origins and theories about its meaning. Once again, there's a big difference in the kind of normal-science data collection depicted in Prometheus and The Thing. With one or two notable exceptions, the explorers in Prometheus don't do organized data collection at all - they blunder around almost completely without context.

How (Not) to Do Normal Science

In Prometheus, after spending two whole years approaching the alien world LV223, the crew lands and begins exploring without more than a cursory survey. We know this because the ship arrives on Christmas, breaks orbit, flies around seemingly at random until one of our heroes leaps from his chair because he's sighted a straight line formation, and then the ship lands, disgorging a crew of explorers eager to open their Christmas presents. We can deduce from this that less than a day has passed from arrival to landing, which is not enough time to do enough orbits to complete a full planetary survey. We can furthermore deduce that the ship had no preplanned route because then the destination would not have been enough of a surprise for our hero to leap out of his chair (despite the seat-belt sign) and redirect the landing. Once the Prometheus lands, the crew performs only a modest atmospheric survey before striking out for the nearest ruin. In true heroic space opera style this ruin just happens to have a full stock of all the interesting things that they might want to encounter, and as a moviegoer, I wasn't bothered by that. But it's not science.

Planets are big. Really big. The surface area of the Earth is half a billon square kilometers. The surface area of a smaller world, one possibly more like LV223, is just under a hundred fifty million square kilometers. You're not likely to find anything interesting just by wandering around for a few hours at roughly the speed of sound. The crew is shown to encounter a nasty storm because they don't plan ahead, but even an archaeological site is too big to stumble about hoping to find something, much less the mammoth Valley of the Kings style complex the Prometheus lands in. Here the movie both fails and succeeds at showing the protagonists doing science: they blunder out on the surface despite having perfectly good mapping technology (well, speaking as this is one of my actual areas of expertise, really awesome mapping technology), which they later use to map the inside of a structure, enabling one of the movie's key discoveries. (The other key discovery is made as a result of David spending two years studying ancient languages so he can decipher and act on alien hieroglyphs, and he has his own motives for deliberately keeping the other characters in the dark, so props to the filmmakers there: he's doing bad science for his team, but shown to be doing good science on his own, for clearly explained motives).

SO ANYWAY, a scientific expedition would have been mapping from the beginning to provide context for observations and to direct explorations. A scientific expedition would have released an army of small satellites to map the surface; left them up to predict weather; launched a probe to assess ground conditions; and, once they landed, launched that awesome flock of mapping drones to guide them to the target. The structure of the movie could have remained the same - and still shown science.

The Thing provides an example of precisely this behavior. The explorers in The Thing don't stumble across it. They're in Antarctica on a long geological survey expedition to extract ice cores. They've mapped the region so thoroughly that spurious radio transmissions spark their curiosity. Once the ship and alien are found, they survey the area carefully in both horizontal and vertical elevation, build maps, assess the structure of the ice, and set up a careful archeological dig. When the paleontologist Kate arrives, they can tell her where the spacecraft and alien are, roughly how long the spacecraft has been there, and even estimate the fracturability of the ice is like around the specimen based on geological surveys, and already have collected all the necessary equipment. Kate is so impressed she exclaims that the crew of the base doesn't really need her. And maybe they don't. But they're careful scientists on the verge of a momentous discovery, and they don't want to screw it up.

Real Scientists Don't Take off Their Helmets

Speaking of screwing up momentous discoveries, here's a pro tip: don't take off your helmet on an alien world, even if you think the atmosphere is safe, if you later plan to collect biological samples and compare them with human DNA, as the crew does in Prometheus. Humans are constantly flaking off bits of skin and breathing out droplets of moisture filled with cells and fragments of cells, and taking off a helmet could irrevocably contaminate the environment. The filmmakers can't even point to the idea that you could tell human from alien DNA because ultimately chemicals are chemicals: the way you tell human from alien DNA is to collect and sequence it, and in an alien environment filled with unknown chemicals, human-deposited samples could quickly break down into something that looked alien. You might get lucky ... but you probably won't. Upon reading this article, one of my colleagues complained to me that this was an unfair criticism because it's a simply a filmmaker's convention to let the audience see the faces of the actors, but regardless of whether you buy that for the purpose of making an engaging space opera with great performances by fine actors, it nevertheless portrays these scientists in a very bad light. No crew of careful scientists is going to take off their helmets, even if they think they've mysteriously found a breathable atmosphere.

The movie Avatar gets this right when, even in a dense jungle, one character notices another open a sample container with his mouth (to keep his hands free) and points out that he's contaminated the sample. The Thing also addresses the same issue: one key point of contention between paleontologist Kate and her superior Sander is that Sander wants to take a sample to confirm that their find is alien and that Kate does not because she doesn't want the sample to be contaminated. Both are right: Kate's more cautious approach preserves the sample, while Sander's more experienced approach would have protected the priority of his discovery from other labs if it really was alien, or let them all down early if the sample just was some oddly frozen Earth animal. My sympathy is with Kate, but my money is actually on Sander here: with a discovery as important as finding alien life on Earth, it's critically important to exclude as soon as possible the chance that what we've found is actually a contorted yak. More than enough of the sample remained undisturbed, and likely uncontaminated, to guard against Kate's fears.

Unfortunately, neither the crew of Prometheus or The Thing get the chance to be proved lucky or right.

How (Not) to Do Abnormal Science

Abnormal science is my term for what scientists do when "everything's gone to pot" and lives are on the line. This happens more often than you might think: the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill are two recent examples. Strictly speaking, what happens in abnormal science isn't science, that is, the controlled collection of data designed to enhance the state of human knowledge. Instead, it's crisis mitigation, a mixture of first responses, disaster management and improvisational engineering designed to blunt the unfolding harm. Even engineering isn't science; it's a procedure for tackling a problem by methodically collecting what's known to set constraints on a library of best practices that are used to develop solutions. The tools of science may get used in the improvisational engineering that happens after a disaster, but it's rarely a controlled study: instead, what gets used are the collected data, the models, the experimental methods and more importantly the precautions that scientists use to keep themselves from getting hurt.

One scientific precaution often applied in abnormal science which Prometheus and The Thing both get right is quarantine. When dealing with a destructive transmissible condition, like an infectious organism or a poisonous material, the first thing to do is to quarantine it: isolate the destructive force until it's neutralized, until the vector of spread is stopped, or until the potential targets are hardened or inoculated. After understandable moments of incredulity, both the crew of the Prometheus and The Thing implement quarantines to stop the spread of the biological agent and then decisively up the ante once its full spread is known.

The next scientific precaution applied in abnormal science is putting the health of team members first. So, for goodness's sake, if you've opened your helmet on an alien world, start feeling under the weather, and then see a tentacle poke out of your eye, don't shrug it off, put your helmet back on and venture out onto a hostile alien world as part of a rescue mission! On scientific expeditions, ill crewmembers do not go on data collection missions, nor do they go on rescue missions. That's just putting yourself and everyone else around you in danger - and the character in question in Prometheus pays with his life for it. In The Thing, in contrast, when a character gets mildly sick after an initial altercation, the team immediately prepares to medivac him to safety (this is before the need for a quarantine is known).

Another precaution observed in abnormal science is full information sharing. In both the Fukushima Daiishi and Deepwater Horizon disasters, lack of information sharing slowed down the potential response to the disaster - though in the Fukushima case it was a result of the general chaos of a country-rocking earthquake while in the Deepwater Horizon case it was a deliberate and in some cases criminal effort at information hiding in an attempt to create positive spin. The Prometheus crew has even the Deepwater Horizon event beat. On a relatively small ship, there are no less than seven distinct groups, all of whom hide critical information from each other - sometimes when there's not even a good motivation to. (For the record, these groups are (1) the mission sponsor Weyland who hides himself and the real mission from the crew, (2) the mission leader Meredith who's working for and against Weyland, (3) the android David who's both working with and hiding information from Weyland, Meredith, the crew and everyone else, (4) the regular scientific crew trying to do their jobs, (5) the Captain who then directs the crew via a comlink and then hides information for no clear reason, (6) the scientist Charlie who hides information about his illness from the crew and his colleague and lover Elizabeth, and finally (7) Elizabeth, who like the crew is just trying to do her job, but ends up having to hide information about her alien "pregnancy" from them to retain freedom of action). There are good story reasons why everyone ends up being so opposed, but as an example of how to do science or manage a disaster ... well, let's say predictable shenanigans ensue.

In The Thing, in contrast, there are three groups: Kate, who has a conservative approach, Sander, who has a studious approach, and everyone else. Once the shit hits the fan, both Kate and Sander share their views with everyone in multiple all-hands meetings (though Sander does at one point try to have a closed door meeting with Kate to sort things out). Sander pushes for a calm, methodical approach, which Kate initially resists but then participates with, helping her make key discoveries which end up detecting the alien presence relatively early. Then Kate pushes for a quarantine approach, which Sander resists but then participates in, volunteering key ideas which the alien force thinks are good enough to try to sabotage. Only at the end, when Kate suggests a test that the uninfected Sander knows full well will result in a false positive result for him, do they really get at serious loggerheads - but they're not given a chance to resolve this, as the science ends and the action movie starts at that point.

The Importance of Peer Review

I enjoyed Prometheus. I saw it twice. I'll buy it on DVD or Blu-Ray or something. I loved its focus on big questions, which it raised and explored and didn't always answer. It was pretty and gory and pretty gory. It pulled off the fair trick of adding absolute classic scenes to the horror genre, like Elizabeth's self-administered Ceasarean section, and absolute classic scenes to the scifi genre, like the David in the star map sequence - and perhaps even the crashing alien spacecraft inexorably rolling towards our heroes counts as both classic horror and classic science fiction at the same time.

But as Ridley Scott was quoted as saying, Prometheus was a movie, not a science lesson. The Thing is too. Like Prometheus, the accuracy of the scientific backdrop of The Thing is a full spectrum mixture of dead on correct (the vastness of space) to questionable (where do the biological constructs created by the black goo in Prometheus get their added mass? how can the Thing possibly be so smart that it can simulate whole humans so well that no-one can tell them apart?) to genre tropes (faster than light travel, alien life being compatible with human life) to downright absurd (humanoid aliens creating human life on Earth, hyperintelligent alien monsters expert at imitation screaming and physically assaulting people rather than simply making them coffee laced with Thing cells).

I'm not going to pretend either movie got it right. Neither Prometheus nor The Thing are good sources of scientific facts --- both include a great deal of cinematic fantasy.

But one of them can teach you how to do science.

-the Centaur

Pictured: a mashup of The Thing and Prometheus's movie posters, salsa'd under fair use guidelines.

Thanks to: Jim Davies, Keiko O'Leary, and Gordon Shippey for commenting on early drafts of this article. Many of the good ideas are theirs, but the remaining errors are my own.